The road ahead: Challenges for EV adoption in Australia

11

August

2025

1

min read

Electric Vehicle (EV) uptake in Australia remains slower than most developed countries. York Park Group explores the policy landscape and some of the main barriers to EV adoption in Australia, and why understanding perceptions and beliefs are critical when it comes to communications.

Key Facts and Figures

- Average EV range is over 400km whilst average daily car travel is only 33 km

- 10.3 per cent of new cars purchased in Australia in the first half of 2025 were EVs

- 41 per cent of Australians say they intend to purchase an EV in the future

- 70 to 85 per cent of EV charging happens at home; 10 to 20 per cent of charging happens at public charging stations

- There are 3,700 public charging stations compared to 6,600 petrol stations across Australia

- 70 per cent of EV owners reported encountering at least one inoperable charger in a six-month period

- EVs in Australia lose an average of 58.8 per cent of their value within five years, compared to 45.6 per cent for petrol and diesel cars over the same period

York Park Group's Thoughts

Within the context of the upcoming Productivity Roundtable and the proposed introduction of a Road User Charge, the subsidies received by EV purchasers have once again received national attention.

Like most aspects of emissions reduction policy, there is an element of ideology within the debate, shifting public discourse from ‘facts and figures’ to ‘beliefs and opinions’.

However, in any debate between beliefs and facts, beliefs often cannot be changed by the facts. Rather, they are changed by experience (for example, driving an EV) or by broader societal shifts, where your beliefs become an outlier in your direct peer circle.

Creating society-wide change is complex and challenging, and requires a mix of understanding of society perceptions, targeted messaging and consistent and repetitive communications.

EV uptake in Australia in the coming years will be an interesting example of consumer marketing, policy effectiveness and political advocacy working in collaboration – whichever way it goes.

The Policy Landscape - Regulations and Incentives

National Electric Vehicle Strategy (NVES)

Released in April 2023, NEVS was Australia’s first comprehensive national EV roadmap. Its three key objectives are:

- Increasing the supply of affordable and accessible EVs;

- Establishing enabling infrastructure, including charging networks; and

- Encouraging demand for EVs among consumers.

The centrepiece of NEVS was the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard which was passed in May 2024 and has just commenced enforcement in July 2025. It sets CO₂ emissions caps for new vehicle fleets, and penalises manufacturers for exceeding the limits.

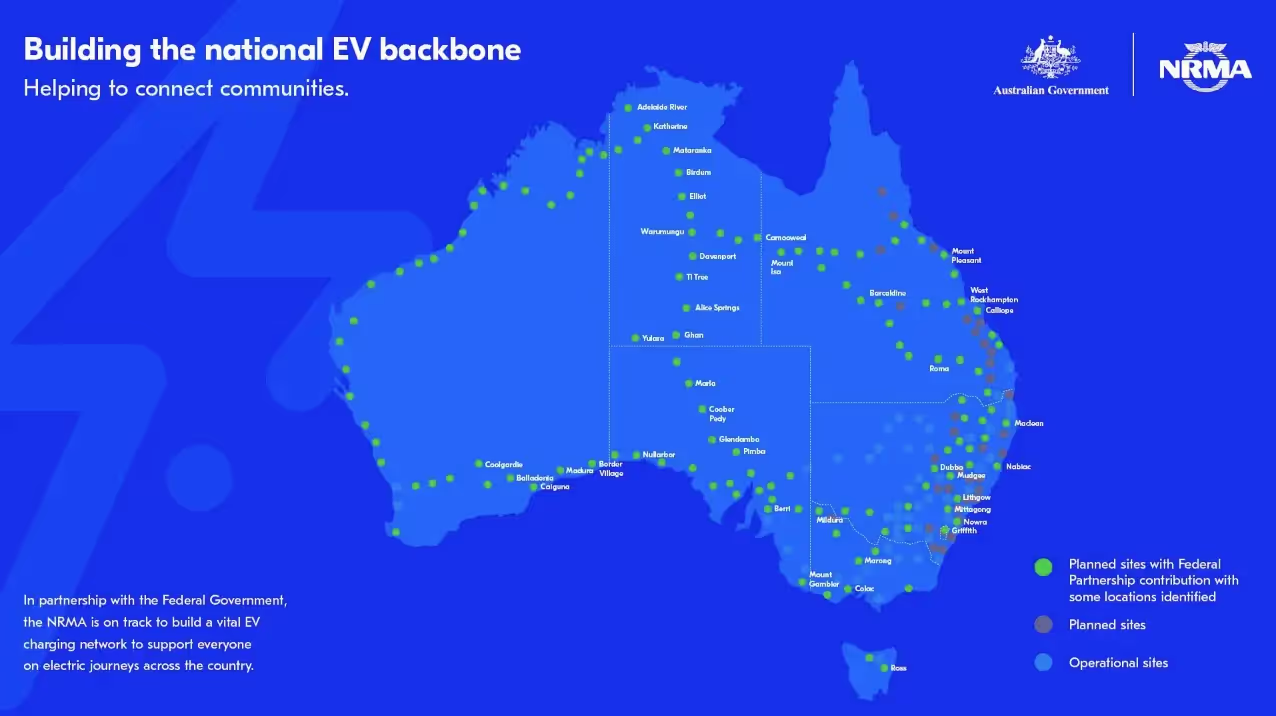

National EV Charging Network – Driving the Nation

In 2023, Minister for Climate Change and Energy, Chris Bowen MP, announced a $39.3 million investment to install 117 fast EV charging sites along national highways across the country.

This was a partnership with the NRMA (National Roads Motor Association), which matched the investment.

These chargers – capable of up to 350 kW – are strategically located to tackle blackspots and range anxiety, ensuring long distance travel such as Darwin to Perth or Brisbane to Tennant Creek is feasible for EVs.

The National EV Charging Network is due to be finished in 2026.

Fringe Benefits Scheme

A significant financial incentive is the Fringe Benefits Tax (FBT) exemption on eligible EVs beneath the Luxury Car Tax threshold.

This policy was introduced in 2022 and allows employers to pay no Fringe Benefits Tax on EVs.

However, as of April 2025, PHEVs (hybrids) have been excluded from this exemption.

Road User Charge

The Federal Government is actively considering a national Road User Charge (RUC) for electric vehicles.

Treasurer the Hon Dr Jim Chalmers has flagged the RUC as a key reform to replace declining fuel excise revenue, which currently funds road infrastructure.

The proposed charge would be distance-based and set at a rate broadly equivalent to the fuel excise paid by petrol and diesel drivers, with potential concessions or rebates for regional and outer-suburban motorists who have limited public transport options.

Details are still under consultation, and the Government is working with the States and Territories to develop a national framework.

Challenges – Perceptions

1. Range Anxiety vs Charger Anxiety

The term “range anxiety” is widely used as a reason people are hesitant to buy EVs, however it potentially mischaracterises the problem.

The average EV can now travel over 400km per charge, far exceeding the 33km daily average for most drivers. However, the fear of running out of charge persists, especially among those yet to own an EV.

This fear can be more accurately described as “Charger Anxiety”: uncertainty about finding a working, accessible, and compatible public charger.

Unlike petrol stations, public EV chargers:

- Are often broken (70 per cent of EV users reported encountering this within 6 months)

- Lack staff, lighting, or surveillance, making users feel unsafe and/or vulnerable

- Have inconsistent plug types; compare this to cars which all use the same petrol nozzle.

As of May 2025, up to 13 per cent of registered public EV chargers across the country were unavailable to use.

Despite the fact that Australia has a minimum uptime requirement of 98 per cent for public chargers, there are still relatively high levels of inoperable chargers.

As ‘The Driven’ reported this year:

“The problem is no one seems to be following up on whether chargers are meeting those minimums, nor putting enough capital towards maintenance, and charge point operators are seeing the aftermath of bad practices in their industry”.

The Electric Vehicle Council has advocated for greater government involvement in mandating minimum uptime standards to improve confidence.

2. Pressure on the Grid

Is Australia’s electricity transmission grid ready for greater uptake in EVs?

A rise in EV adoption would bring with it a surge in electricity demand, but whether the grid is ready to cope depends on how smartly the transition is managed.

Forecasts from major network providers like Ausgrid and Endeavour Energy suggest EV charging demand could increase more than thirtyfold within the next five years, driven by national targets aiming for 50 per cent of new car sales to be electric by 2030.

At its core, the problem is one of timing: If every EV owner charges their car as soon as they get home – i.e. typically during peak evening demand – the grid will be placed under intense pressure.

The average EV battery, to be fully charged, consumes three times as much power as an average Australian household uses in a day. Projections indicate that if every car on Australia's roads today were to become electric, it would result in approximately a 15 per cent increase in overall electricity demand.

However, a 2022 report by the Electric Vehicle Council noted that the majority of at-home EV charging happens in the middle of the night or the middle of the day, with little charging occurring during peak electricity use periods.

This is a significant mitigating factor; many owners are already charging during the day using solar power, or overnight to take advantage of cheaper, off-peak electricity rates. This behaviour would significantly minimise impacts on the grid.

A longer-term solution lies in the potential for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology. This enables electric vehicles (EVs) to not only draw power from the grid for charging, but also to send excess energy back into the grid.

This was successfully demonstrated in 2024, when a storm tore down power lines west of Melbourne, forcing a power station and a wind farm to shut down. About 500km away in Canberra, charging stations began draining the batteries of ACT Government electric vehicles in Canberra and feeding the power back into the national grid. In total, 16 vehicles provided 107kW of support to the grid.

To put this in perspective, the energy provided by those 16 vehicles would power roughly 129 households for the day – whilst miniscule compared to the 90,000 households that lost power, it did demonstrate the potential for this technology in the future.

3. Resale Value and the Second-Hand Market

The depreciation of EVs in Australia presents a significant challenge to broader adoption, as they do not retain their value as well as petrol cars.

In 2025, EVs are estimated to lose an average of 58.8 per cent of their value within five years, compared to approximately 45.6 per cent for petrol and diesel cars over the same period. For a $60,000 car, this would mean a resale value of $32,640 for petrol cars versus $24,720 for electric.

This depreciation is influenced by a few factors, but largely rapid advancements in battery technology can quickly make older models seem outdated, contributing to consumer apprehension about battery life and longevity.

Australia has a strong second-hand car market, and it is still the most common way people purchase cars – for every new car that is purchased, 1.7 used cars are sold.

Therefore, while petrol cars are still on the road, for anyone looking to sell their vehicle or purchase one second-hand – this is expected to remain a barrier.

10

February

2026

Regional aviation in Australia: The key drivers behind current government reviews

Read news article

10

February

2026

Regional aviation in Australia: The key drivers behind current government reviews

Download White Paper

4

February

2026

.webp)

York Park Group launches transaction communications service

Read news article

4

February

2026

.webp)

York Park Group launches transaction communications service

Download White Paper